Recipes

By Ron Broglio

Spells are nothing but poems intended to write something new on the face of reality. Warren Ellis

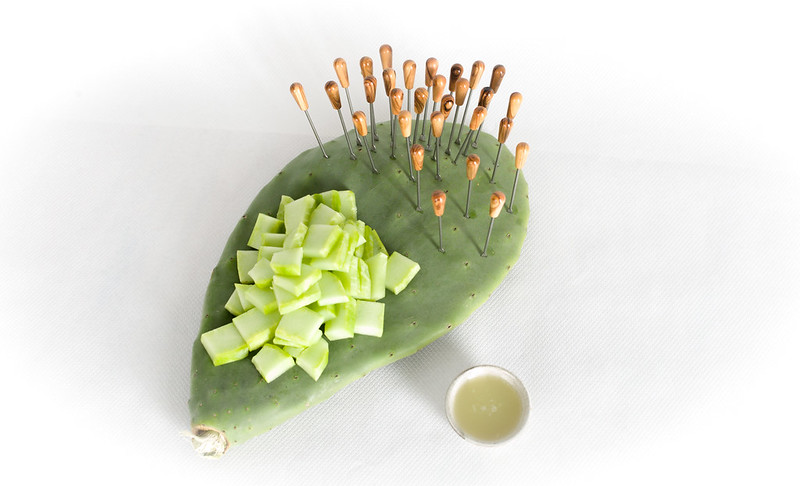

Paddle Cactus

(aka Nopales)

The paddle cactus is a desert version of Southern okra with a similar texture and taste. You can buy paddle cactus at Latino grocery stores or if you have your own access to these plants, you can take a few paddles from your plant.

- Remove the spines and edges from each paddle. Place the paddle on a cutting board. With a sharp knife, cut away the edges and scrape off the spines. Some folks use protective gloves to help avoid being poked by the spines and some use pliers to pull off the poking spines before scrapping away the eye of the spine.

- Rinse the paddles and cut them into bite size rectangles.

- In a large pot heat enough water to cover the paddles (but don’t add the catus yet, wait until the water boils)

- Once the water is boiling, add cactus and toss in an onion cut in large chunks, a few cloves garlic, and salt.

- Boil uncovered for 8-10 minutes until the cactus is tender. Keep an eye on the pot. The cactus may produce a foam; so be mindful it doesn’t spill over the pot. The cactus will •Once tender, drain from pot and pat dry with a towel.

- Paddle cactus are very good in scrambled eggs or in a Southwestern bean salad. You can also lightly sauté them with onions and tomatoes, top with cilantro, and serve as a salad or dip.

Water, water, everywhere, Nor any drop to drink.” It might seem counter-intuitive, but Coleridge’s famous line from the Ancient Mariner could also apply to the desert. Even in some of the driest places on earth, the air holds thousands of litres of fresh water that have remained tantalisingly inaccessible. Until now. Scientists at MIT and the University of California at Berkeley have created a device that can suck water from the air. Even better: it’s solar-powered. So, even in the most remote, arid deserts it can harvest drinking water from the atmosphere. Charlotte Edmond, The solar-powered tech that generates water out of desert air

Mesquite Flour

Mesquite flour is highly nutritious with a sweet, caramel-like taste. It is best used mixed with other flour such as wheat at a ratio of ¼ to mesquite to ¾ wheat flour. It works well in pancakes, cornbread, and smoothies. I can be added in smaller quantities 1/6th to 5/6th in making bread.

Mesquite Flour is gluten free and high in protein (between 11-17% depending on the variety of mesquite) and high in soluble fiber. It is also a good source of calcium, magnesium, potassium, iron, and zinc.

To make Mesquite flour:

- Gather dried mesquite pods (also called “beans”). These are the beige pods that look like long snap beans. You can use the whole long pod!

- Harvest before the first rain of summer or in late summer or fall which is long after the rainy season. This is important to avoid aflatoxin contamination—the black spots of mold found on the pod. Pods still on the tree are safest. Ripe pods from the tree require only a slight tug.

- Dry the pods.To ensure pods are dry, you can lay them on a drying rack for a few days or put them in the oven at low temperature to dry. Alternatively, you can use a dehydrator.

- Mill the pods. Using a blender or Vitamix, grind the pods into a flour. Sift the flour and return the rough unsifted parts to the blender for further milling.

- Store in a jar in a dry place and best used within a few months.

Alternative uses for pods. Using 4 quarts water to 1 pound beans, cook on a low heat for 12 hours. Then strain and reduce by boiling until it is a thick syrup. You can use the syrup as you would any sweetener, syrup, or honey—for example, add in smoothies or tea.

The bean thrives on vines even in the hottest months, and packs more protein and other nutrients than its more common relatives, like pinto and kidney beans. Arizona’s earliest residents grew teparies for thousands of years, but in recent history, the beans were at risk of shriveling into obscurity. “We have to preserve the past. We have to preserve our traditions,” Button said. “We have to respect the responsibility that we have.” The beans come in a spectrum of colors: white, brown, black, and speckled blue like robin’s eggs. “There’s a way, that I can’t describe in words, where teparies to me taste like the desert itself,” [tepary bean evangelist Gary Paul Nabhan] said. “They have this nuttiness and this resilience.” (…) Nabhan believes the drought-tolerant teparies could become a solution for growing food in a hotter and drier Arizona. Traditionally, the Tohono O'odham grow teparies on monsoon rains alone. “I think we’re going to see agriculture of the future looking much more in harmony with the desert rather than always being in struggle with a desert existence,” Nabhan said.“ Mariana Dale, Arizona's Tepary Beans

Dust and Shadow Reader Vol. 1. Previous: walking exercises. Next: fieldnotes 2.

References: bibliography